12345

12345

filter by Title A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z [all]

| ID | Title | Description | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 359 | Chinese contributors to the Chinese Economic Journal (educational institutions) | Based on the following dataset, the attached graphs explore Chinese contributors' educational institutions (the university in which they received their highest degree) in the Chinese Economic Monthly/Journal between 1924 and 1936, all periods included (1) and per period (2, 3). We relied on R package "ggplot2" to build these bar charts. |

| 360 | Contributors to the Chinese Economic Journal (institutional positions) | Based on the following dataset, the attached graphs explore authors' institutional positions at the time they contributed to the Chinese Economic Monthly/Journal, per period (1, 2, 3) and sector of activity (4, 5). Relying on R package "ggplot2", we alternatively used faceted, stacked and dodged bar charts. The last set of graphs (6) provides a more detailed analysis of institutions, arranged by sector of activity and period. |

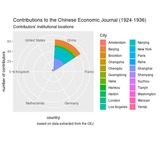

| 361 | Contributors to the Chinese Economic Journal (country and city of occupation) | Based on the following dataset, the attached graphs aim to map the countries and cities in which the authors worked at the time they contributed to the Chinese Economic Monthly/Journal, all periods included (1, 2) and per period (3, 4). Relying on R package "ggplot2", we alternatively used bar charts and polar coordinates. |

| 362 | Contributions to the Chinese Economic Journal (importance and duration) | Based on the following dataset, the attached graphs visualize the number of articles that individual authors contributed to the Chinese Economic Monthly/Journal, in relation to the duration of their contribution (number of years). We relied on R package "ggplot2" to build the scattered plots. In addition, we test multiple factors that may potentially account for their varying contribution to the journal: nationality (2), field of specialization (3), level of education (4), and institutional position (5). |

| 363 | Contributions to the Chinese Economic Journal (contributors' degree of specialization) | Based on the following dataset, the attached graphs visualize the number of articles that individual authors contributed to the Chinese Economic Monthly/Journal, in relation to the range of topics they addressed (number of distinct topics, on a scale ranging from 1 to 7), all periods included (1) and per period (2). We relied on R package "ggplot2" to build the scattered plots. |

| 364 | Contributions to the Chinese Economic Journal (degree of specialization and contributors' nationality) | Based on the following dataset, the attached graphs aim to test the potential influence of contributions' nationality on the number of articles they contributed to the Chinese Economic Monthly/Journal, in relation to the range of topics they addressed (number of distinct topics, on a scale ranging from 1 to 7), all periods included (1) and per period (2). We relied on R package "ggplot2" to build the scattered plots. |

| 365 | Contributions to the Chinese Economic Journal (degree and contributors' field of specialization) | Based on the following dataset, the attached graphs aim to test the potential influence of contributions' educational background (the academic disipline in which they graduated) on the number of articles they contributed to the Chinese Economic Monthly/Journal, in relation to the range of topics they addressed (number of distinct topics, on a scale ranging from 1 to 7), all periods included (1) and per period (2). We relied on R package "ggplot2" to build the scattered plots. |

| 366 | Contributions to the Chinese Economic Journal (degree of specialization and contributors' level of education) | Based on the following dataset, the attached graphs aim to test the potential influence of contributions' educational background (the highest academic degree they obtained) on the number of articles they contributed to the Chinese Economic Monthly/Journal, in relation to the range of topics they addressed (number of distinct topics, on a scale ranging from 1 to 7), all periods included (1) and per period (2). We relied on R package "ggplot2" to build the scattered plots. |

| 367 | Contributions to the Chinese Economic Journal (degree of specialization and contributors' institutional position) | Based on the following dataset, the attached graphs aim to test the potential influence of contributions' institutional position (sector of activity) on the number of articles they contributed to the Chinese Economic Monthly/Journal, in relation to the range of topics they addressed (number of distinct topics, on a scale ranging from 1 to 7), all periods included (1) and per period (2). We relied on R package "ggplot2" to build the scattered plots. |

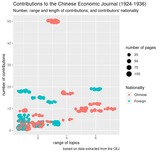

| 368 | Contributions to the Chinese Economic Journal (degree of specialization, length of articles and contributors' nationality) | Based on the following dataset, the attached graphs aim to test the potential influence of contributions' nationality on the number of articles they contributed to the Chinese Economic Monthly/Journal, in relation to the range of topics they addressed (number of distinct topics, on a scale ranging from 1 to 7) and the length of articles they contributed (measured by the number of pages), all periods included (1) and per period (2). We relied on R package "ggplot2" to build the scattered plots. |

| 369 | Contributions to the Chinese Economic Journal (degree of specialization and length of articles) | Based on the following dataset, the attached graphs visualize the number of articles that individual authors contributed to the Chinese Economic Monthly/Journal, in relation to the range of topics they addressed (number of distinct topics, on a scale ranging from 1 to 7) and the length of articles they contributed (measured by the number of pages, visualized by the varying size of dots), all periods included (1) and per period (2). We relied on R package "ggplot2" to build the scattered plots. |

| 370 | Contributions to the Chinese Economic Journal (degree of specialization, length of articles and contributors' fields of specialization) | Based on the following dataset, the attached graphs aim to test the potential influence of contributions' educational backbround (the academic disciplines in which they graduated) on the number of articles they contributed to the Chinese Economic Monthly/Journal, in relation to the length of articles (measured by the number of pages, visualized by the varying size of dots), and the range of topics they addressed (number of distinct topics, on a scale ranging from 1 to 7), all periods included (1) and per period (2). We relied on R package "ggplot2" to build the scattered plots. |

| 371 | Contributions to the Chinese Economic Journal (degree of specialization, length of articles and contributors' level of education) | Based on the following dataset, the attached graphs aim to test the potential influence of contributions' educational backbround (the highest academic degree they obtained) on the number of articles they contributed to the Chinese Economic Monthly/Journal, in relation to the length of articles (measured by the number of pages, visualized by the varying size of dots), and the range of topics they addressed (number of distinct topics, on a scale ranging from 1 to 7), all periods included (1) and per period (2). We relied on R package "ggplot2" to build the scattered plots. |

| 372 | Contributions to the Chinese Economic Journal (degree of specialization, length of articles and contributors' institutional position) | Based on the following dataset, the attached graphs aim to test the potential influence of contributions' institutional positions (sector of activity) on the number of articles they contributed to the Chinese Economic Monthly/Journal, in relation to the length of articles (measured by the number of pages, visualized by the varying size of dots), and the range of topics they addressed (number of distinct topics, on a scale ranging from 1 to 7), all periods included (1) and per period (2). We relied on R package "ggplot2" to build the scattered plots. |

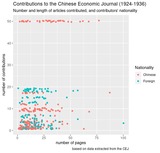

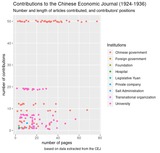

| 373 | Contributions to the Chinese Economic Journal (length of articles and contributors' nationality) | Based on the following dataset, the attached graphs aim to test the potential influence of contributions' nationality on the number of articles they contributed to the Chinese Economic Monthly/Journal, in relation to the length of articles (measured by the number of pages), all periods included (1) and per period (2). We relied on R package "ggplot2" to build the scattered plots. |

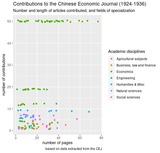

| 374 | Contributions to the Chinese Economic Journal (length of articles and contributors' fields of specialization) | Based on the following dataset, the attached graphs aim to test the potential influence of contributions' educational backbround (the academic disciplines in which they graduated) on the number of articles they contributed to the Chinese Economic Monthly/Journal, in relation to the length of articles (measured by the number of pages, visualized by the varying size of dots), all periods included (1) and per period (2). We relied on R package "ggplot2" to build the scattered plots. |

| 375 | Contributions to the Chinese Economic Journal (length of articles and contributors' level of education) | Based on the following dataset, the attached graphs aim to test the potential influence of contributions' educational backbround (the highest academic degree they obtained) on the number of articles they contributed to the Chinese Economic Monthly/Journal, in relation to the length of articles (measured by the number of pages, visualized by the varying size of dots), all periods included (1) and per period (2). We relied on R package "ggplot2" to build the scattered plots. |

| 376 | Contributions to the Chinese Economic Journal (length of articles and contributors' institutional position) | Based on the following dataset, the attached graphs aim to test the potential influence of contributions' institutional positions (sector of activity) on the number of articles they contributed to the Chinese Economic Monthly/Journal, in relation to the length of articles (measured by the number of pages, visualized by the varying size of dots), all periods included (1) and per period (2). We relied on R package "ggplot2" to build the scattered plots. |

| 377 | Evolution of membership at the Shanghai Rotary Club | Based on data extracted from Rotary International Archives (record of club memberships gains and losses, meeting attendance, membership attendance card). The original dataset is avaialble here. We used R package "ggplot2" to build this graph. |

| 378 | Meeting attendance at the Shanghai Rotary Club | Based on data extracted from Rotary International Archives (record of club memberships gains and losses, meeting attendance, membership attendance card). The first graph is based on the average monthly attendance, whereas the second graph is based on the actual number of attendees. The original dataset is avaialble here. We used R package "ggplot2" to build these graphs. |

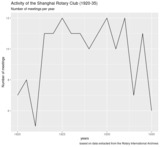

| 379 | Regular meetings of the Shanghai Rotary Club | Based on data extracted from Rotary International Archives (record of club memberships gains and losses, meeting attendance, membership attendance card), this graph traces the total number of meetings hold (or recorded) per year over the period 1920-35. The original dataset is avaialble here. We used R package "ggplot2" to build this graph. |

| 380 | Time series of membership at the Shanghai Rotary Club | Based on the following dataset, the attached time series trace the evolution of membership at the Rotary Club of Shanghai over the period May 1920-September 1935 (inclusive).

|

| 381 | Time series of attendance percentage at the Shanghai Rotary Club | Based on the following dataset, the attached time series trace the evolution of attendance percentage at the Rotary Club of Shanghai over the period May 1920-September 1935 (inclusive).

NB Since the attendance time series cannot be described as an additive model, it was not possible to decompose it. |

| 382 | Time series of attendance at the Shanghai Rotary Club | Based on the following dataset, the attached time series trace the evolution of attendance (number of attendees) at the Rotary Club of Shanghai over the period May 1920-September 1935 (inclusive).

NB Since the attendance time series cannot be described as an additive model, it was not possible to decompose it. |

| 383 | Time series of meetings at the Shanghai Rotary Club | Based on the following dataset, the attached time series trace the evolution of meetings (monthly number of meetings per year) at the Rotary Club of Shanghai over the period May 1920-September 1935 (inclusive).

|

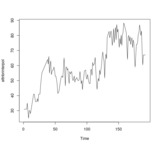

| 384 | Number of pages in the Chinese Economic Journal: A Time Series Analysis | Based on the following dataset, the attached time series trace the evolution in the volume (number of pages per issue) of the Chinese Economic Journal over the period November 1923-June 1937 (inclusive).

|

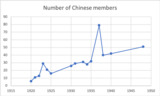

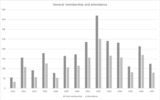

| 385 | Chinese membership in the Rotary Club of Shanghai | The attached graphs show the growth of Chinese membership in the Rotary Club of Shanghai from 1920 to 1948. The first graph reflect the growth in number while the two others show the proportion of Chinese members compared to foreign members and total membership. Data comes from rosters of members and membership lists available in the Archives of Rotary International, Evanston, Ill. The tables used for building the graphs are available in the "Tables" Section. The graphs reveal that Chinese membership increased gradually over time. There was a steady growth between 1920 (only one member, Y.C. Tong) and 1948 (51 members), with a short peak in 1937 (80). In the aftermath of the outbreak of the Sino-Japanese war in August 1937, Chinese membership declined significantly. It was halved during the first year of the war, falling to 40 members in 1938, 43 in 1939 and finally 30 in 1945. During the postwar years, however, the incorporation of members resumed, and Chinese membership climbed to 51 members in July 1948, a few months before the establishment of the Chinese-speaking Rotary Club of Shanghai West. The growth of Chinese membership is even more striking when compared to the total membership. On average, Chinese members represented 29% of all Shanghai Rotarians during the entire period. While they amounted to less than 20% of the total membership until 1923, their share rose to more than one quarter between 1923 and 1935 (except in 1924, with 18%) and reached a peak just before the outbreak of the war (61%). For the first time, Chinese members represented the majority in the club. This figure fell to 32% in 1938 but rose again to 44% in 1939, 40% in 1945 and 42% in 1948. In the end, the war reversed the proportion of Chinese and foreign members. As many foreigners left the country immediately after the bombings in August 1937, and even more after Pearl Harbor (December 1941), Chinese members remained close to the majority from 1938 onwards. |

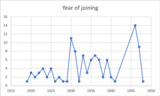

| 386 | Chinese Rotarians: Joining year and duration of membership | The attached graphs show the yearly distribution of Chinese members' incorporation into the Rotary Club of Shanghai and the duration of their membership. Data comes from rosters of members and membership lists available in the Archives of Rotary International, Evanston, Ill. The tables used for building the graphs are available in the "Tables" Section. The graphs reveal that the admission of Chinese nationals remained low during the first decade (1919-1929), with less than five new members per year, and only one (Y.C. Tong) during the first year (1920). There was a first peak in 1930 (11 new members). Between 1933 and 1940, the number of new members per year remained unstable, oscillating between a minimum of three (1934) and a maximum of seven (1936). The incorporation of Chinese members resumed after the war and reached its highest peak in 1945 (14 new members that year).* Since most members joined after 1930, and given their high professional mobility and the politically unstable situation in Shanghai and China more generally, it is quite remarkable that three members maintained their membership for over twenty years. C.T. Wang (Wang Zhenting) held the record, with twenty-eight years of membership, followed by Imin Hsu and Percy Kwok (21 years). Twenty-four members (22%) remained for more than ten years, and eighteen (17%) from five to ten years. The majority, however, stayed less than five years (53 members), including fourteen who left within a year. *Due to the lack of rosters between 1925-1930 and 1940-1945, however, we cannot assess the exact date of incorporation for members who joined in the 1920s and during the war. In reality, the trend was probably smoother than shown on the graph. |

| 387 | Chinese Rotarians: Classification | The attached graphs offer various ways of visualizing the professional distribution of Chinese members of the Rotary Club of Shanghai (funnel, bar charts, tree maps). Our analysis is based on a simplified version of the standard classification of professions devised by Rotary International in the early 1920s. The four first graphs shows the general distribution (all periods included), while the last one shows the distribution of professions across the three major periods we delineated in the history of the club from the perspective of Chinese membership: (1) the beginning of the club and weak Chinese membership prior to 1930 (2) growth of Chinese membership and climax of the club in the 1930s (1930-1937) (3) war and postwar period (1938-1948). Data comes from rosters of members and membership lists available in the Archives of Rotary International, Evanston, Ill. The tables used for building the graphs are available in the "Tables" Section. The graphs reveal that the medical profession was by far the best represented occupation among Chinese Rotarians (20 members, 16%). The chemical industry and financial services (including banking, insurance and savings banks) formed the second largest professional group (11 members, 9% each), followed by printing/publishing (newspapers, publishing houses), and transportation/storage (9 members, 7% each). The fourth group included four main sectors represented by six Rotarians each (5%): the cotton industry, associations, education/hospitals, and local government. The latter referred mostly to officers in the municipality of Greater Shanghai, but there was also one member who worked for the Shanghai Municipal Council and two for the provincial government. The next group (representing less than 5% of Chinese members) comprised five branches of activities that were also well-developed in Shanghai during the Republican period: building construction and materials (including architecture) (five members, 4%), general merchandising (especially department stores), tourism (hotels, restaurants), silk industry (which probably reflected the proximity of Suzhou, major center for silk production), and machinery (four Rotarians, 3% each). Next, recreation (movie theatres) and communication services (radio, advertising) employed three Rotarians each (2%). The last group was made up of less-developed industries that employed two Rotarians each: metal, electrical, wool and clothing. The remaining Rotarians were scattered across miscellaneous sectors: fine arts, ceramic, coal and food industry. Two industrial branches made only a short appearance in the reorganized club in 1945 (grain and tobacco leaf distribution). In addition, there were two lawyers (H.C. Mei and W. Hung) and three honorary members, either government officials (C.T. Wang, Wellington Koo) or Y.M.C.A. leaders (Fong Sec). Although the by-laws stated that “Persons holding elective or appointive public office, for a specified term only, shall not be eligible to active membership as a representative of such office” it is interesting to notice that the Mayor of Shanghai (Wu Tiesheng) was a member of the club while he was in office, and that honorary members C.T. Wang and Wellington Koo were concurrently holding prominent positions in the central government at the time of their membership. The war did not affect much the professional distribution of members, except for the disappearance of the Printing/Publishing class - a longstanding, major sector of activity in Shanghai. After the war, therefore, medicine, the chemical industry, banking/finance and the cotton/textile industry still topped the list in the reorganized club in 1945. There were no major changes in 1948, except that associations had gained in importance due to the postwar reconstruction work, ranking third after medicine and the chemical industry, equaling banking and superseding the cotton industry. What can we draw from this analysis? The classification structure of Chinese Rotarians reflected quite faithfully the local industrial fabric and the social-professional make-up of Chinese elites in Shanghai during the Republican period. Indeed, the Rotary Club of Shanghai functioned as a microcosm of Shanghai business and professional elites, with only one (ideally the best) representative of each branch of activity, as the by-laws requested. It is interesting to notice, however, that some sectors remained utterly missing – especially agriculture-related activities – sectors that were poorly developed in Shanghai and among Chinese Westernized elites more particularly. |

| 388 | The Rotary Club of Shanghai West: Classification of members | The attached graphs offer various ways of visualizing the professional distribution of Chinese members of the Rotary Club of Shanghai West (Chinese speaking-speaking club established in 1948 in parallel to the original Rotary Club of Shanghai). Our analysis is based on a simplified version of the standard classification of professions devised by Rotary International in the early 1920s. Data comes from the membership lists available in the Archives of Rotary International, Evanston, Ill. The tables used for building the graphs are available in the "Tables" Section. The graphs reveals that the professional distribution of members was very similar to that of the Rotary Club of Shanghai. Chemical industry and medicine ranked first, followed by general merchandising, education, and tourism, also important sectors in the English-speaking club. Some professional groups that were prominent among Shanghai Rotarians, however, went missing in the Chinese-speaking club, namely cotton and silk industries, building and construction, machinery equipment and recreational services. Despite these slight differences, however, the postwar club of Shanghai West did not differ much from its foreign counterpart. |

| 389 | Chinese Rotarians: Year of birth and age at joining | The attached graphs show the distribution of Chinese Rotarians' year of birth and examine at what age they joined the two clubs (the original Rotary Club of Shanghai estbalished in 1919 and the Chinese-speaking Rotary Club of shanghai West established in 1948). To compute their age, we simply compared their year of birth with the year they joined the club. Membership data (year of joining) comes from rosters available in the Archives of Rotary International, Evanston, Ill. Birth data comes from the series of Who's Who available through the Integrated Information System on Modern and Contemporary Characters (IISMCC) hosted by the Academia Sinica’s Institute of Modern History. The tables used for building the graphs are available in the "Tables" Section. The graphs reveal that the majority of Chinese Rotarians in Shanghai was born between 1880 and 1896 (31, 53%), with two peaks in 1884 and 1896 (5 members each year) (cf. table/graph). Seven Rotarians were born before 1880 (12%) and the seventeen remaining between 1897 and 1912. To sum up, the majority was born before the Revolution and the establishment of the Republic (1911-2). They grew up in the late 1890s-early 1900s and were in their twenties or thirties when Rotary was introduced in China. The oldest member was fifty-nine and the youngest was barely seven years-old when the first club was established in Shanghai in 1919. The distribution of birth dates further suggests that most of them received their education after the imperial examination system was abolished in 1905, which means that they were likely to attend Western-style universities in China or abroad in order to earn their academic credentials, as we will elaborate later. The age distribution graph confirms that most new members were in their thirties or forties when they joined the club (43 members, 78%). Four members joined in their twenties, twenty-one in their thirties (35%) and twenty-two in their forties (37%). Only seven members were over fifty, among whom three were older than sixty. In other words, Chinese Rotarians in Shanghai formed a young, active population made up of mature men at the height of their professional life. Although the Rotary Club of Shanghai West was established some thirty-one years later than the pioneering one, its members were not much younger than their predecessors. In fact, they belonged to the same generation. Among the eight members we identified, three were born in the 1890s, two in 1902, one in 1904 and one in 1906 (cf. table/graph). Overall, they joined the club a slightly later age than their counterparts of the foreign-speaking club. All members were over 40 when they joined, three being over 50 (but no one over 60). |

| 390 | Chinese Rotarians: Provincial origins | The attached graphs offer various ways of visualizing the distribution of Chinese Rotarians' provincial origins (place of birth). Data comes from the series of Who's Who available through the Integrated Information System on Modern and Contemporary Characters (IISMCC) hosted by the Academia Sinica’s Institute of Modern History. The tables used for building the graphs are available in the "Tables" Section. The distribution of members’ provincial origin reveals a clear pattern of geographical proximity. Most Chinese Rotarians in Shanghai came from Jiangsu (19 members, 33%, among whom 13 were born in Shanghai proper) or the bordering provinces of Zhejiang (11 members, 19%) and Guangdong (10 members, 10%). Ten members, however, came from more remote regions, namely Hubei (3), Hebei (2), Jiangxi (2), Fujian (2). Five were born abroad, in Singapore, Australia, Canada, and two in the United States. Overall, our analysis is consistent with previous studies of Westernized Chinese, which have demonstrated that the large majority of American-trained Chinese, more specifically, were originally from Guangdong, Jiangsu and Zhejiang provinces.

|

| 392 | Chinese Rotarians: Country of education | The attached graphs offer various ways of visualizing the distribution of Chinese Rotarians' country of education. They reveal the dominance of American-returned students. Data comes from the series of Who's Who available through the Integrated Information System on Modern and Contemporary Characters (IISMCC) hosted by the Academia Sinica’s Institute of Modern History. The tables used for building the graphs are available in the "Tables" Section.

|

| 393 | Chinese Rotarians: University of education | The attached graphs examine the universities in which Chinese Rotarians trained in the United States pursued their studies (we selected only the institutions in which they obtained their highest academic degree). Data comes from the series of Who's Who available through the Integrated Information System on Modern and Contemporary Characters (IISMCC) hosted by the Academia Sinica’s Institute of Modern History. The tables used for building the graphs are available in the "Tables" Section. Among the forty-one US-trained Rotarians, one-third (13) was graduated from Columbia University, followed by the University of Pennsylvania (6 graduates). The next group comprises six elite universities that trained two Chinese each - Harvard, Lehigh (Pennsylvania), Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), Chicago, Michigan and Yale. The remaining Rotarians were scattered across other elite universities - Cornell, Johns Hopkins, New York, Princeton, Cincinnati, Texas Agricultural and Mechanical College, University of Cincinnati, of Illinois, and Jones Commercial College (Chicago). Interestingly, there was one representative from the early Chinese Educational Mission (1872-1881), namely Y.C. Tong (the first Chinese to join the Rotary Club of Shanghai in 1920), who upon his return to China served in the late Qing Telegraph Administration. In sum, most Shanghai Rotarians were educated in top-ranking American universities, mostly on the Eastern coast of the United States. Only one member received a private education at home - a residual practice of imperial educational system.

|

| 394 | Chinese Rotarians: Academic degree | The attached graphs examine Chinese Rotarians' level of education (based on the highest academic degree they earned). Data comes from the series of Who's Who available through the Integrated Information System on Modern and Contemporary Characters (IISMCC) hosted by the Academia Sinica’s Institute of Modern History. The tables used for building the graphs are available in the "Tables" Section. The graphs reveal the high level of qualifications of Chinese Rotarians, with a remarkably large number of Master and Ph.D graduates.

|

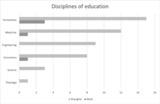

| 395 | Chinese Rotarians: Academic major | The attached graphs examine the discipline in which Chinese Rotarians graduated (based on the highest academic degree they earned). Data comes from the series of Who's Who available through the Integrated Information System on Modern and Contemporary Characters (IISMCC) hosted by the Academia Sinica’s Institute of Modern History. The tables used for building the graphs are available in the "Tables" Section. The graphs reveal that the humanities (foreign languages, education, law, journalism, political science) clearly dominated the educational choices of these "Americanized" Chinese. Medical studies came next due to the overwhelming representation of physicians in the club.

|

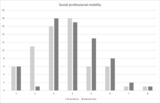

| 396 | Chinese Rotarians: Social-professional mobility | The attached graphs aim to examine the social-professional mobility of Chinese Rotarians. The two first graphs show the number of positions (salaried and not salaried) they took during their professional career. The last one examine theit mobility across various sectors of activity (number of positions taken in different sectors of activity). Data comes from the series of Who's Who available through the Integrated Information System on Modern and Contemporary Characters (IISMCC) hosted by the Academia Sinica’s Institute of Modern History. The tables used for building the graphs are available in the "Tables" Section. Overal, Chinese Rotarians demonstrated a high degree of social-professsional mobility, holding multiple positions across a wide range of sectors. The total number of positions (salaried or not) ranged from 1 to 65. Most of them (26 individuals, 39%) hold at least ten and up to twenty positions during their career. The next most important group hold between twenty and thirty positions (14 individuals, 21%). Thirteen members hold more than thirty positions, among whom six took more fifty positions (names) and two over sixty (names). We recorded less than ten positions for twelve Rotarians. Based on our classification of institutions into eleven sectors of activity (associations, private company, government, hospital, international organizations, church, army, court, political party, other), we observe that Chinese Rotarians also demonstrated a high degree of inter-professional mobility, with forty-eight members (72%) working across three to five sectors of activity. Eleven Rotarians (11%) served in more than five and up to eight different categories of institutions over their entire career. |

| 397 | Chinese Rotarians: Institutional affiliation | The attached graphs examine the institutions that employed Chinese Rotarians. Data comes from the series of Who's Who available through the Integrated Information System on Modern and Contemporary Characters (IISMCC) hosted by the Academia Sinica’s Institute of Modern History. The tables used for building the graphs are available in the "Tables" Section. For analytical purposes, we classified the institutions into eleven categories (sorted by decreasing order of importance) (cf. graph) : associations (221 positions, 29%), private company (118, 15%), government and hospital (45, 6% each), international organizations (17, 2%), church (10, 1%), army (9, 1%), court (6, 1%), and other (6 positions, 1%), including political party (2 positions, less than 1%). Based on this classification, we observe that associations were by far the best represented category, followed private companies, universities, government and hospitals. Except for associations, the distribution reflects the professional composition of the population of Chinese Rotarians we described earlier. While any Rotarian from any profession could hold positions in private companies (as owners, board members or managers), serve in the government (either as ministers, technical advisers or members of commission) or teach in universities, positions in hospitals reflect more specifically the prominence of medical practitioners in the club. International organizations referred mostly to diplomats, but also to Rotarians who attended international conferences, such as the Peace Conference in Versailles (1919-20) or the Washington disarmament conference (1921), as government official delegates or technical advisers. This suggests that the freshly established Republican government was eager to capitalize on foreign-trained elites because of their superior linguistic skills. Positions in the army referred to senior Rotarians who were old enough to participate in the Revolution (1911) or later served in the Nationalist Army, especially during the Northern Expedition (1926-27). Military positions often combined with political responsibilities as provincial governors. Positions in court applied exclusively to lawyers or graduates in law. That only two Rotarians were affiliated to political parties is hardly surprising. Indeed, Americanized Chinese were known for being politically more conservative than their counterparts educated in China, Japan or Europe (especially France). In addition, this perfectly fitted with Rotary’s principle of political neutrality.The two occurrences of political affiliation referred to membership in the Tongmenhui (early revolutionary party) or in the Nationalist Guomindang. There were no Communists among Rotarians, but this reflects a more general trend among American-educated elites in China.

|

| 398 | Chinese Rotarians: Geographical mobility | The attached graphs aim to examine the geographical mobility of Chinese Rotarians based on the number of different places their visited during their life. Data comes from the series of Who's Who available through the Integrated Information System on Modern and Contemporary Characters (IISMCC) hosted by the Academia Sinica’s Institute of Modern History. The tables used for building the graphs are available in the "Tables" Section. From the graphs, we observe that Chinese Rotarians showed a high degree of geographical mobility during their life, which reflects their multilingual proficiency and their multicultural identity, rooted in their education abroad and for some of them, their overseas background. They traveled a lot not only in foreign countries but also in China proper. Of a total 1310 different places visited by 66 individuals, 75% were located in China (975), 20% (263) in North America (the United States, including Hawaii, and Canada), 40 in Europe, 32 in Asia or Australia (2). Most of them moved from their native place at an early age. Among the most mobile Rotarians, eight worked or lived in over ten different places, and twenty-seven individuals visited from five to ten places.

|

| 399 | Chinese Rotarian officers: number and level of offices | The following graphs examine the number and level of offices that Chinese Rotarians took in the service of the club. We distinguished three main level of service (from bottom to top): committee, board and Rotary International. The two first graphs offer two different ways of visualizing the number of offices taken in relation to the number of officers (graph line and funnel). The third one shows the distribution of offices across the various levels of service while the fourth one examines in more detail the nature of positions. The last graph ranks the top Chinese Rotarian officers based on their respective number of positions in the club. Original data comes principally from Rotary International archives and the table we built for conducting the statistical analyses are available in the "Tables" section. Relying on the rosters and lists of officers available in Rotary archives, we identified 69 Chinese Rotarians who held 266 positions in the club between 1920 and 1948. While the majority (35) served at the committee level only, twenty-eight members took higher positions as officers or board members, and six were appointed to supreme positions in the organization as Chinese representatives of Rotary International (RI) in Chicago, Ill. Early Chinese members took high positions as officers prior to 1930. The first Chinese treasurer was elected in 1920 (Y.C. Tong), the first vice-president in 1926 (Fonc F. Sec), and the first president in 1927 (Luther M. Jee). The level of position increased in the 1930s, with three Chinese presidents elected: Fong F. Sec (1931-2), Percy Chu (1934-5) and W.H. Tan (1937-8). Mid-level positions as committee members also boomed during these years, which means that although all Chinese Rotarians could not reach the highest ranks, a growing number of ordinary members became more actively involved in the life of the club. Individually, forty-seven officers totaled less than five positions, thirteen between five to ten, and four over ten (cf. table 2). Fong Sec ranked first with twenty-seven positions, followed by Percy Kwok (17), Percy Chu (16) and L.M. Jee (10) (cf table 3). There was a strong correlation between the number and the level of positions taken (cf. table 4). Thirty-four Rotarians held sixty-six positions as board members, some of them being reelected for two or more successive years: Percy Chu (1928-35), Fong Sec (1926-35), T.K. Ho (1925-1938), Habin Jsu (1924-6), Percy Kwok (1931-5), V.F. Lam (1925-31), H.C. Mei (1933-35), S.D. Ren (1923, 1935). Four Chinese served as treasurer (10 positions), three of them being reelected three times to that position (K.P. Chen, Percy Chu and V.F. Lam). Over its entire existence (1919-52), the Rotary Club of Shanghai elected five Chinese presidents. Three of them topped the list of the twelve most active officers in the history of the club (L.M. Jee, Fong Sec and Percy Chu). In addition to the four presidents already mentioned (Jee, Fong, Chu, Tan), William Sung was elected the year before the club ceased functioning during the war (1941). He was reelected to that position when the club was reorganized in November 1945. Fong and Chu had previously served as vice-president (Fong in 1926 and 1928, Percy Chu in 1930-1931). The latter also became sergeant-at-arms after retiring as president in 1935. Four presidents were appointed to international positions in the organization. In 1922, Fong was sent as the first Chinese delegate to the Annual Convention of Rotary International (RI) in Los Angeles. He was later elected member of the board of directors of Rotary International (1932-4) and district governor for two consecutive years (1936-8). L.M. Jee was appointed commissioner of Rotary International in China for three consecutive years (1927-30). Although he never took positions in the Rotary Club of Shanghai itself, C.T. Wang was also appointed commissioner of Rotary International and first district governor when the 81st district (covering China and the Philippines) was officially established in 1935. As such, he was specifically in charge of arranging the Annual Convention of Rotary International that took place for the first time in China (Shanghai) in April 1936. During the war, he served as RI advisor to China (1942-6) and was elected board member (1944-6) and even vice-president of Rotary International (1945-6). In the postwar years, he was again appointed district governor (1946-7, 1948-9) and RI advisor for China, Hongkong and Macao (1951-3). W.H. Tan also acted as district governor (1940-1, 1947-8) and governor’s representative (1942) in the war and postwar years. William Sung served briefly as acting district governor in 1941.

|

| 400 | Chinese Rotarians: Service in committees | The following graphs examine in detail the responsibilities that Chinese Rotarians took in the various committees of the club, using various visualization techniques (bar charts, tree maps). Original data comes principally from Rotary International archives and their tabulation is available in the "Tables" section. The graphs reveal that Chinese Rotarians served primarily in the Charities and Community Service committees (21), followed by Fellowship (18), Schools and Education (17) and Public Affairs (15). Thirteen Chinese were involved in the Rotary Extension committee, which played a crucial role in the formation of new Rotary clubs in China. Chinese Rotarians were also well-represented in the International Service committee (in charge of relations with Rotary International) and the Finance committee (responsible for the budget of the club), with 12 positions each. The prominence of Chinese members in the Finance committee reflected more generally the weight of Chinese bankers and financiers in the club. The Boy’s Work committee also ranked high despite its foreign origins. Chinese Rotarians who were concurrently involved in the Y.M.C.A movement often served in this committee. Chinese members were less involved in committees dealing with the internal affairs of the club (club service, business ethics, membership and classification, attendance), which represented less than ten positions each.

|

| 401 | Pagoda corpus | The two graphs provides basic information on the corpus of Pagoda we were able to reconstruct from the archives of Rotary International. Pagoda was the official organ of the Rotary Club of Shanghai. Published every week, it represents a rich source we have on the life of the club, providing information on regular meetings (topic and attendance), meetings of the board of directors and special committees, anedoctes on members, information on other clubs in China, and miscellaneous stories. The tabulated data we used for conducting our analyses is available in the "Tables" section. The first graph shows the number of issues available for each year, while the second one shows the number of pages in each issue. Although the existing collection of Pagoda remains incomplete, the thirty-one issues at our disposal are quite regularly distributed over time, with an average of two issues per year between 1919 and 1937, except for the years 1920 and 1932 (two bountiful years with three issues) and four years of scarcity with only one issue available (1921, 1924, 1928, 1937). The number of pages ranges from one in 1919 to fourteen in 1930 and 1934, with an average of ten to twelve. |

| 402 | Membership, Attendance and Absence at Rotary meetings (after "The Pagoda") | The following graphs shows the evolution of attendance at regular meetings of the Rotary Club of Shanghai. The first graph compares the general attendance with the total membership (all nationalities included). The two other graphs examines Chinese absence at meetings (absence without excuse) in relation to the total number of absentees. Data comes from the corpus of Pagoda we were able to reconstruct from Rotary International archives. The tabulated data we used for conducting our analyses is available in the "Tables" section. The first graph reveals that general attendance was rather irregular over time. In terms of percentage of total membership, attendance never exceeded 70% prior to 1930, with a several drop in 1928 (46%). It rose in the 1930s and peaked in 1935-1936 (74%), while Yinson Lee was chairman of the Programme committee. No data was available for the war and postwar years. Symmetrically, absence without excuse was very irregular over time, with a remarkable drop in 1925 and a severe peak in 1932. As shown on the second and third graphs, Chinese absentees followed the general trend, except in the early years, since the club included very few Chinese members at the time. Their absence peaked in 1925, which suggests that Chinese Rotarians were largely responsible for the general drop in attendance that year. There was second peak of absence in 1934 (46%) and a third, the most important, in 1937 (50%). |

| 403 | The Shanghai Rotary Club in the press | The following graphs provides basic information on the press corpus we built for analyzing the presence of the Rotary Club of Shanghai in the local press. The tabulated data we used for building the graphs is available in the "Tables" section. The first bar chart summarizes the most important information related to the corpus (documents and distribution across newspapers over time). The two next graphs show the number of occurrences (words or bags of words) and documents (articles) that mention the Rotary Club of Shanghai in the press, while the remaining ones examine in more detail the distribution of ocurrences and documents (articles) across the three major English-language newspapers. Built by combining two sets of keywords ("Shanghai Rotary Club" and "The Rotary Club of Shanghai"), this corpus contains all the press articles that mention the Rotary Club of Shanghai in three major English-language newspapers: North-China Herald, Millard's Review (and its successor China Weekly/Monthly Review), and China Press. We selected these newspapers because they are the ones that best publicized the activities of the club and enjoyed an appreciable continuity of publication. We also selected them because they are easily accessible in digital format on the ProQuest collection of Chinese newspapers, which makes them processable for large-scale analyses. For building the corpus, we used the R Studio package “enpchina” developed by Pierre Magistry, our computational linguist in the European Research Council (ERC) Project “Elites, networks and power modern China". This package was specifically tailored for the ProQuest collection of Chinese newspapers. Drawing on Natural Language Processing (NLP) techniques, this package offers a set of advanced tools for exploring large corpora of historical newspapers, especially complex queries, statistical analysis, extraction of name entities, network analysis and graph visualization. The keywords were carefully selected so as to reduce noise deriving from the fuzzy meaning of the word “rotary” (which literally means “wheel” or “mill”) and to remove articles dealing with Rotary clubs outside of Shanghai. Based on this query, we obtained a corpus of 949 occurrences distributed across 865 documents (articles) and six different publications (mostly three: China Press, China Weekly Review, North-China Herald), ranging from 1919 to 1948, with a peak in 1936.

|

| 404 | Chinese Rotarians: Activity index | The following graphs aim to examine Chinese Rotarians‘ varying degree of involvement in the club, based on their presence in newspaper reports of Rotary meetings. The tabulated data we used for obtaining the graphs is available in the "Tables" section. Our method for measuring the degree of participation into the club consisted in three steps:

The two first graphs show the top 10 and 20 Rotarians mentioned in the press, ranked by decreasing number of occurrences. The two additional graphs retain ambiguous cases, providing a confidence index for ranking the same individuals (top 15 and 20). Building on this activity index, three major groups emerged: eleven “highly active” Rotarians (over 10 occurrences, with Fong Sec. leading far ahead with 75 occurrences), eight “moderately active” (5 to 10), and twenty-two “less active” members (under 5 occurrences). We should add to this list the 67 members who never appeared in newspapers and therefore can be considered as “inactive” or “invisible” members. Unsurprisingly, the varying degree of activity is directly correlated to their service in the club, i.e. the number of and the level of positions they took in Rotary. The index partly reflects the roles that members were expected to play according to the by-laws. For instance, the president was supposed to chair every meeting, and this largely accounts for the high scores of the three presidents Fong, Chu and Jee. The constitution, however, does not explain everything. Our findings reveal irregular cases that point to either discrepancies between the rules and their application, or to inevitable gaps in the available documentation. For instance, president Tan lags far behind less prominent members. Conversely, Wellington Koo, an honorary member who never took any positions in the club and barely attended its regular meetings, nonetheless ranks high on the list. |

| 405 | The Rotary Club of Shanghai: Program of meetings under Chinese leadership | The following graphs aim to examine whether the program of the Rotary Club of Shanghai was given more "Chinese flavor" while Chinese members took leadership positions in the club. We defined two main criteria for gauging the "Chineseness" of the program: the nature of events and the nationality of speakers invited at regular meetings. We also analyzed the topic of lectures in connection with speakers’ nationality and affiliation. We extracted the original information from press reports of meetings in three major local newspapers (North-China Herald, China Weekly Review, China Press). The tabulated data we used for conducting these analyses are available in the "Tables" Section. The two first graphs show the distribution between Chinese and foreign speakers under four Chinese presidents - L.M. Jee (1927-8), Fong Sec (1931-2), Percy Chu (1934-5), and W.H. Tan (1937-8) - and under Lee's chairmanship of the program committee (1934-6), respectively. The third graph shows the distribution of topics among Chinese and foreign speakers, while the last one examines their institutional affiliation. From these analyses we can draw four major conclusions:

In the end, efforts to sinicize the club program proved insufficient as long as English remained the dominant language and as organizers continued to rely on their network of overwhelming foreign connections. |